Over the last two decades the study of African peoples and their descendants in the UK has increased dramatically, with research from communities and academia contributing to the understanding. There is now a wide range of sources from printed material to websites informing on a wide variety of African focused issues. This section is a very brief history and only skims the surface of African peoples in Scotland. It primarily serves as putting into context that African peoples have been part of Scotland’s heritage dating back into pre-history. No political statements or motives are implied.

Ancient History (3600 BCE – 500 CE)

The ScotlandsDNA Project, which studied the genetics of native Scots, has identified that 1% of the population are descended from the Berber and Tuareg tribesmen of the Sahara. This dates to the early pre-historic human migration from the East Africa to other parts of the world; but our earliest recorded history was

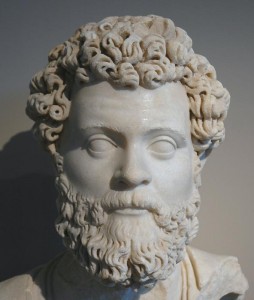

by the Romans. When the Caledonians (early inhabitants of Scotland) invaded south into Roman Britain in AD208, the Roman Emperor Septimius Severus (AD 145-211) travelled to York to begin a military campaign to counter the attacks. Septimius Severus was born in Libya. His father was Libyan and his mother Roman. Due to his ancestors being Roman citizens, he was allowed to be educated in Rome. He started his career as a lawyer, before becoming a senator and was involved in many of Rome’s military campaigns. He was described by the physician Galen as “a man of such energy ... wise and successful ... that he left no battle except as victor”.

Evidence from archaeological sites also points to other Africans, from Roman legions, having lived and died in Britain. Roman legions were made of a wide range of ethnic groups including African, and it is possible that some of those people remained and settled in Britain.

Early Modern to Mid Modern Period (1500-1914)

To move further along in history we have the accounts of King James IV of Scotland who had African Moors in his court. In 1505 several Africans were recorded as being with the King’s Court for a Shrove Tuesday celebration, including a drummer and dancers. Six years later the accounts of the King’s Treasurer recorded the buying of clothes and material for specific Moor women such as “Blak Margaret” who was given a gown costing 48 shillings (about £500 today). Further, during the reign of James VI it is recorded that a Black Moor was paid to help pull the chariots during celebrations to mark the birth of James’s eldest son, Henry Frederick. Nothing more is known about this Moor except that he lived in Edinburgh.

Britain being an island had a great dependence on the sea for both exports and imports. The merchant and naval vessels acquired their own particular type of migrant worker, many of whom stayed in the ports while awaiting their next employment. Inevitably relationships were fostered between the local inhabitants and the migrant workers leading to changes in direction of their lives.

Scotland has had a long history associated with Africa, particularly since the 18th century. Though movement of peoples had occurred throughout previous centuries, it was during the 18th and 19th centuries that large numbers of people began moving about the world. a large number of African peoples were forcibly moved to different parts of the world during the 18th century in the worst aspects of human exploitation, and Scotland played a part in this. But, it was also a major supporter of the anti-slavery movement, and by 1778 it became illegal to own a slave in Scotland, the first country to pass such legislation. In 1807 the British Parliament finally abolished the trading of slaves in the British Empire, but slaves working on plantations in British colonies were not ‘emancipated’ until 1833. It would take the American Civil War (1861 to 1865) to bring about the end of slavery in those colonies, though it was still perpetuated by the Arabs and Portuguese in Africa, against which the missionary David Livingstone campaigned.

The role of Scotland in the 18th century slave trade is only now being re-evaluated. Out of the four million slaves in the British Empire, 4500 to 5000 slaves were traded from Scottish ports. Scottish landlords, particularly in Jamaica, owned a large number of the plantations around the Caribbean, though many were absentee owners preferring to remain in Scotland. These landlords themselves brought and retained African servants in Scotland. It was considered fashionable at the time for wealthy families to have a young black boy or girl ‘attending’ on them. They were usually baptised and given Christian names with the adopted surname of the families they lived with. This makes it difficult to trace and identify the numbers of individuals who came to Scotland.

One such African, who was traced, was from Guinea, by the name of Scipio Kennedy, whom Captain Douglas of Mains brought to Scotland in 1702. In 1705 when the Captain’s daughter married John Kennedy, the married couple employed Scipio, and he signed a contract for 20 years and was given the surname of Kennedy. In 1725 he signed a new contract, which survives in the National Archives of Scotland, and was given the right to look for better work, if he so wished, and agreed to remain with the Kennedys until then. But Scipio was not without character. In 1728 it is recorded that he was brought before the local Kirk session, along with others, to be publicly rebuked for his sins with Jean Fergusson, that is, he was having sexual relations with her. But, several years later Scipio married another local girl, Margaret Gray, and had several children with her. The family was given a plot of land where they remained until his death in 1774.

Mary Jane Seacole (1805-1881), née Grant, was the daughter of a Scottish soldier. She was a Jamaican-born woman of Scottish and Creole descent whom, during the Crimean War, set up a “British Hotel” near the battlefront. She described the hotel as “a mess-table and comfortable quarters for sick and convalescent officers,” and provided succour for wounded servicemen on the battlefield. She was posthumously awarded the Jamaican Order of Merit in 1991. In 2004 she was voted the greatest black Briton. Seacole was proud of her Scottish ancestry and called herself a Creole, a term that was commonly used in a racially neutral sense or to refer to the children of white settlers.

The military has had a long tradition of recruiting African people. Antonio Martin joined the Scots Guards in 1806, and Jean Baptiste, a native of Martinique in 1818. Both are shown as musicians in the literature, and part of the larger band, but they would also have seen action as the Scots Guards were involved both in international and local conflicts. Martin died in the Regimental Hospital in 1837 from “water in the chest”; and Baptiste was discharged with full pension suffering from debilitation and deafness in 1841.

Contemporary Period (1914 – present)

The World Wars of the 20th century brought many more African peoples to Scotland, either directly from Africa or from the West Indies and America; some of whom remained. At the end of the First World War the discharged in Glasgow and Edinburgh contributed to a permanent African community as surveys from the 1920s show. One notable was Leo Daniels, an Afro-Canadian, who founded the African Races Association of Glasgow.

Between the world wars, the main impetus for Africans coming to Scotland was for the education, which still remains so today. Scotland has a high regard for education, which is recognised throughout the world and many Africans see this as a stepping-stone to achieve greater things. The students that came to Scotland from Africa contributed to the heritage of the country in founding organisations or giving greater attention to issues in their own countries.

The African students from the University of Edinburgh University were very active in organising the pan-African Conference of 1900, particularly the medical student Moses Da Rocha (1875-1942), from Lagos, Nigeria. He was also the assistant secretary of the African Association, an organization formed in London in 1897 to encourage pan-African unity, particularly throughout the British colonies. Da Rocha did not particularly like his stay in Edinburgh as he was in constant conflict with “bureaucrats and beastly landladies”, as well as “vulgar and unscrupulous Europeanised Negroes”. Another active African student, from Edinburgh, was Richard Akiwande Savage (1874-1935) who became editor of The Gold Coast Leader and President of the Afro-West Indian Literary Society of Edinburgh. He was also a member of the University Student Representative Council from 1898-1900 and regularly contributed to the Scottish press. There was strong political activity amongst the African students in Edinburgh, who actively lobbied politicians and wrote articles in the press both in Britain and West Africa, in promoting African interests and racial equality.

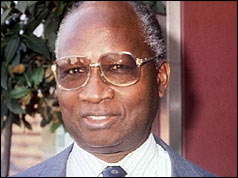

The study of medicine was initially the main attraction for Africans in the late 19th century, and many important figures of African politics studied at University of Glasgow. One of the first graduates was Abdullah Abdurahmann (1872-1902), a Muslim from South Africa, who graduated in 1893 and was a key political leader. His son also received his medical qualification from Glasgow. Allan Kirkland Soga (d. 1938), son of Tiyo Soga, one of the first ordained ministers in South Africa, and Janet Burnside from Scotland, became one of Africa’s leading political and legal thinkers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and founder a political movement that was a forerunner to the African National Congress. After the Second World War, with the developing African economies and independence more Africans came to study in Scotland. By the late 1950s a number of East African Students established their own society in Glasgow called, the Simba Club, which became the East African Students Association in 1963. Dawda Jawara (b. 1924) from Gambia, who studied veterinary medicine at Glasgow University, graduated in 1953. He returned to Gambia and became involved in politics, eventually becoming Prime Minister in 1962. He led the country to independence from the UK in 1965, and continued as President. He was Knighted in 1966, and was awarded an honorary degree by Glasgow University in 1992 for his connection with veterinary science.

Africans in Scotland Today

The recent Census of 2011 identified the growing number of peoples of African origin migrating to Scotland for a wide range of reasons. Of the 5,295,000 people in Scotland, four per cent of people in Scotland were from minority ethnic groups, an increase of two percentage points since 2001. In further detail, the ethnic minority people of Glasgow account for 12% of the city’s population. Edinburgh, together with Aberdeen, has 8% of its total population from minority ethnic groups; and Dundee has 8%. Of these ethnic minorities the African, Caribbean or Black groups made up 1 per cent of the population of Scotland in 2011, with 46,742 of the people from the African continent being resident in Scotland. This was an increase of 28,000 people since 2001. Of those with African descent, nearly 0.2% stated their country of birth was Nigerian, making it the top ninth country of birth outside of the UK, and the only African country named in the top 15 countries.

Education is seen one of the main driving forces of Africans in coming to Scotland since the 19th Century, at first to study medicine, and later expanding into other subject areas. Figures for the UK in 2013 showed that the subjects most likely to be studied were those associated with medicine (44% of UK domiciled black students), followed by business and administrative studies with 16%. In 2012/13, Nigerian students were the third highest country group coming to Scotland, after China and the US.[1] Scotland has always seen the importance of education; having established three Universities by the end of the 15th Century (St. Andrews, Glasgow and Aberdeen), where only two existed in England. The Education Scotland Act of 1496 established the first compulsory schooling for children, albeit for merchants and landowners; but The Education Scotland Act of 1633 established a school for every parish in Scotland, meaning that all children could receive a basic education; and Scotland retained control over its education even after the Union of Kingdoms in 1707.

[1] Figures from Higher Education Statistics Agency.